From Protest to Progress: The Inspiring Journey of Zelema Harris and the Birth of TRIO SES + STEM

“College, man, you must be kidding.”

That is the opening line of the 1972 thesis of Zelema Harris, the founder and first director of the University of Kansas’ Supportive Educational Services, now called TRIO SES + STEM.

The 1960s were tumultuous times, both in the United States and within the University of Kansas. Although the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, the issues faced by Black Americans did not disappear overnight, especially not on campus. KU Black Student Union was keenly aware of this.

In the late 1960s, the KU Black Student Union and its allies advocated and pushed for better inclusion and support for people of color at the university. Efforts included peaceful protests, sit-ins, meetings, newsletters, and walk-outs. Many of the demands were met with resistance from KU administration who insisted the demands were not possible, whether due to monetary constraints, lack of resources, or Kansas law.

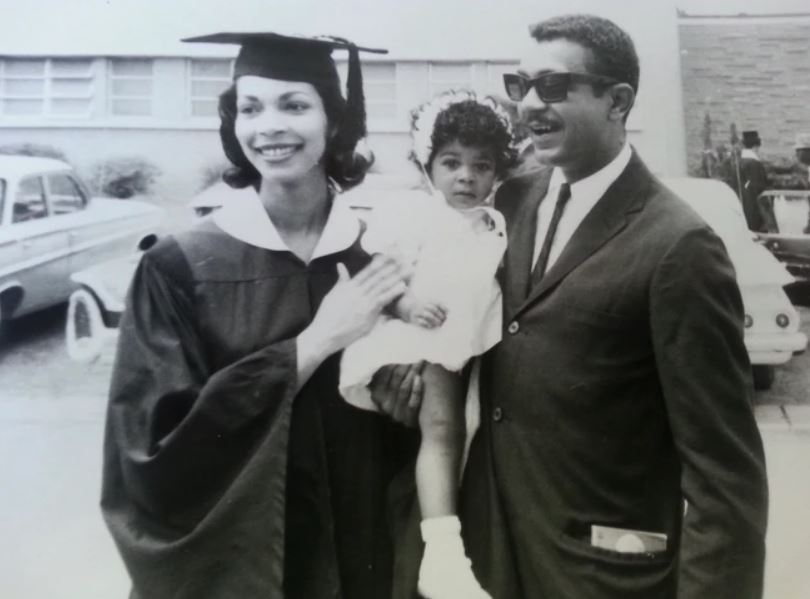

Zelema Harris, who was Zelema Bond at the time, was a graduate student working on her masters. She came to Lawrence with her husband, Horace Bond, and two children when her husband received an assistantship from KU’s speech and theater department.

Although she wasn’t able to regularly attend Black Student Union meetings, she occasionally offered council and advice whenever she could. Harris worked in the admissions department where she evaluated students’ transcripts from other schools to see if any of the courses they took could count for credit at KU. She recalled the white staff being against her being hired.

“When I was hired in 1966 in admissions to support the evaluation office, the director of admissions held a meeting with the staff and said we're going to hire a black girl, and some of them said, ‘we’ll quit. I am not going to work in the office with someone like that.’”

Harris said the director was able to convince the white staff not to quit when he told them about her educational background and experience, and that this moment was one of the many moments where she realized the importance of education.

One of the demands of the Union and its supporters was a program designed to help students of color, mainly Black students, in their journeys as KU students. After agreements between the University and the Black Student Union were met and the Office of Minority Affairs was established, Harris was approached by the administrator of Minority Affairs and Black Student Union members to assume a graduate assistantship and design a program to support Black students in 1969.

Harris accepted despite the pay cut and was given a small space in Watson Library to conduct her work. Her first order of business was to choose a name for the program and learn about other programs in other universities that offered support to minority students.

“I recall sitting in the library on campus with loads of magazine articles spread out, trying to figure out what name to give the program that would not be negative,” Harris said. “And all of a sudden it came to me. Supportive Educational Services. And so that was the name I chose.”

The Office of Minority Affairs dedicated $30,000 to the program. With that money, Harris was able to hire staff, visit other programs, and recruit students to KU and SES. She focused mostly on schools in Kansas and Missouri that had a high percentage of minority students.

“The goal for me was to focus on students who were not the typical college bound student, who had all the academic criteria and who wanted a better life,” Harris said. “They came from poor backgrounds, didn't have a lot of resources they could turn to in their families, and were usually first-generation college going students.”

It was during one of her visits to learn about other programs when she met a student that would help frame her vision for the program and her thesis.

“Mind you, I knew nothing about community colleges at the time. He was a student at a community college outside of San Francisco. I visited their support program, and I asked him how he got here, and he told me that when he was approached to attend college he said ‘College, man, you must be kidding,’ so I used that to frame where I was going with the program,” Harris said.

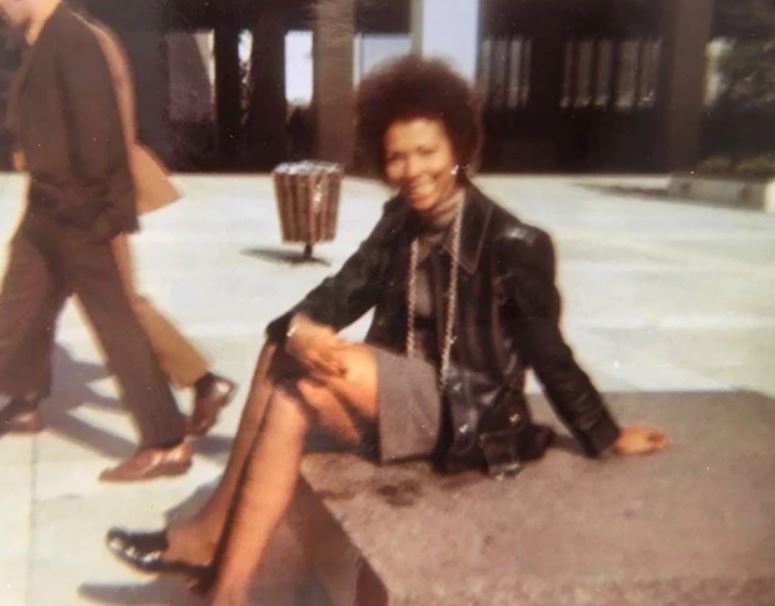

Harris wanted to encourage and inspire minority students to get degrees and educate themselves. She had a radical vision for what the program would do, and she wasn’t afraid to experiment and try things that went against convention.

“I was young and very creative, and I was not hampered by protocol or what couldn't be done as some people are as they become more entrenched in the educational establishment,” Harris said. “I think now about some of the things I was able to do, it was just out of pure ignorance, not knowing. I mean, I would go and talk to the chancellor and the department chair of humanities and talk to them about the inclusion of black authors.”

One of the things Harris implemented was “counselor teachers,” a concept originally from the “Experiment in Higher Education” program from Southern Illinois University. Counselor teachers were graduate students hired by SES to sit in the same classes as SES students to help them with their coursework and offer tutoring outside of class. It was also a way for SES to keep track of students and their progress.

“I borrowed from what worked at other schools. Very little of the program design came from my ingenuity,” Harris said. “Placing it together was the fun part of my job.”

One of the things that did come from Harris was teaching students how to read and understand content in academic writing. SES made sure copies of Evelyn Woods reading comprehension books were made available to students and partnered with the School of Education to offer an intensive summer reading program.

Most of the SES students at the time were Black, and the program often hosted discussions where students were encouraged to talk about their experiences and troubles as minority students. One of the common topics was how minority students were treated by white professors. Harris said she wanted to ensure that they could put their best foot forward and do well despite the discrimination they faced.

“My thing was you cannot control the teacher. What you can control is how you respond,” Harris said. “You often become smarter when you are discriminated against because you're going to find ways to prove yourself.”

Harris was extremely passionate about ensuring students had what they needed in order to succeed at KU. She wasn’t just a program director to the students, she was often their advisor, friend, and family.

“I loved my work. There were no barriers I could not remove and that's the way I've always felt. I don't bother with the barrier if it's over to the side, but if it affects my people, then I will do whatever I can to remove the barrier, go around, and jump over it,” Harris said.

Harris left the program in 1972 after receiving her master with her thesis titled “Supportive Educational Services.” It wasn’t until 1973 that SES got the federal TRIO SSS grant and became TRIO SES. Years later, Harris attended the 20th anniversary of the program. Before the speeches, she was chatting with a medical doctor she didn’t recognize. It wasn’t until he got up to introduce her that she realized it was one of her students from the first SES class and that he was invited to present her as a surprise.

“I wanted to cry I was so filled with emotion. To know what students can do if you believe in them and give them an opportunity and stick with them was very rewarding.”

Harris briefly came back to KU in 1974 for her doctorate degree but did not work with the program. She received her EdD in 1976 and was inducted into the KU Women's Hall of Fame in 1988. After her time at KU, Harris went on to become the president of the Kansas City, Missouri branch of the NAACP, the president of Pioneer Community college, Penn Valley Community College, and Parkland College, the chancellor of St. Louis Community College, and the interim Chancellor of the Pima Community College System in Tucson, AZ. Today, Dr. Harris lives at an independent living facility and writes memoirs on her blog, filled with stories about her life.

Despite all her accomplishments, Harris said that her time at SES was the most special.

“To create a program from scratch was probably the most exciting time of my professional career,” Harris said.

Today, TRIO SES + STEM is housed under the Achievement & Assessment Institute’s Center for Educational Opportunity Programs and serves first-generation students, students with high financial need, and students with disabilities or chronic conditions. The program’s support ranges from academic advising, financial aid, tutoring, career or graduate school preparation, and any needs based on individual circumstances.

Ngondi Kamatuka, the director of CEOP, said that Harris’ contributions to the program help ensure students know they belong at the table.

“Understanding one’s history is the GPS for navigating the future. Dr. Harris is the north star that has guided us over the years and has put us in a better position to ensure marginalized students can enter college and succeed,” Kamatuka said. “Dr. Harris’ vision and commitment has enabled CEOP to be viewed as thought leaders that share our best practices nationally and globally.”

As the person that made the program possible for future generations, Harris’ word of advice to current TRIO SES + STEM students is to persevere.

“Perseverance is not stressed enough. If you don’t get a concept, don’t give up. Whatever class it’s in. Read various sources, look at TikTok and Instagram. Wherever you can learn a concept, use it,” Harris said. “It’s not the smartest people in the world who succeed. It’s those who have a goal in mind and work hard to reach it.”

Last year, TRIO SES + STEM celebrated 50 years of federal funding at KU, making it TRIO’s longest lasting program at the university. Gretchen Heasty, the current director of TRIO SES + STEM, said that she will make sure Dr. Harris’s legacy and advice is shared with current and future TRIO students.

“When Dr. Harris reached out to share her excitement that a successful program still exists, I was deeply grateful to learn about our history at KU and be part of her legacy. Dr. Harris set the stage for advocacy and innovation to support marginalized students, and we strive to follow her example,” Heasty said.

“Dr. Harris’s emphasis on the importance of trusting relationships with students resonated with me. That’s what the TRIO SES & STEM team continues to emphasize today – to be a trusted advisor, friend, and KU TRIO family. We are forever grateful to Dr. Harris for making this program possible and for creating opportunities for TRIO students at KU.”